|

John Bubb |

|

|

|

This article about Saglek appeared in the November 1965 Issue of Command Post

The layout of the article has been adjusted to fit this page. The copy of this article was contributed to my website by Yaro Hospodarsky. |

|

By the very nature of their mission-- detect and identify enemy aircraft far from potential targets in North America-- all radar stations in the Goose Air Defense Sector (GADS) are remote.

However, remote is no longer an absolute word. Today there are varying degrees of that adjective. A new term, unofficial but appropriate, is necessary to describe these isolated outposts where nightmarish weather, complete seclusion and formidable terrain are combined to create remoteness of almost unbelievable proportions. That description, and the term "super remote", fits Saglek AS like a pair of stretch pants.

Each radar Station has its jumping-off point and for Saglek, home of the 924th Aircraft Control and Warning Squadron, it's Goose AB, Labrador. Within minutes after takeoff for the 375-mile trip north, all signs of civilization are replaced by a spectacular panorama of lakes, forests and rivers which stretch as far as the eye can see.

Less than an hour out of Goose, the land looses its lush green look and almost imperceptibly takes on a dull, brown appearance. The solid expanse of trees grows thinner and then disappears entirely. Although to compensate, nature provides a new setting by contrasting rugged coastal mountains against the white-flecked blue of the North Atlantic Ocean, 6,000 feet below.

As our chartered Eastern Provincial Airways (EPA) DC-3 drones up the barren coast, an iceberg is seen floating south with the Labrador Current. Others follow, each strikingly different in size and shape. Passengers speculate about their size until a tanker conveniently appears on the horizon and is dwarfed by the huge icebergs. The south-bound tanker is our first glimpse of civilization since take-off two hours earlier. Then - "There's the radome," cries a civil engineering sergeant, who is visiting Saglek to inspect the runway. Everyone scrambles for their first look and there, brooding across the ocean from its perch atop an 1,800-foot high mountain, sits Saglek. For many minutes, only the single radome is visible but then all buildings come into view as the DC-3 begins letdown procedures. With practiced ease, the EPA crew flies over the base, out past Cape Uivuk and down Saglek Bay. A final left turn and our Gooney Bird settles easily on the 4,800 foot long asphalt runway. |

|

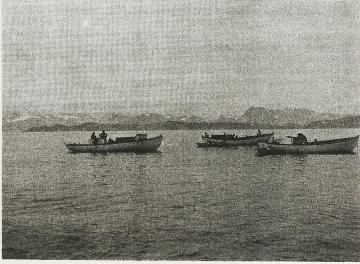

NEIGHBORS IN THE NORTH

Each summer, Saglek is visited by entire Eskimo families from Nain, a small settlement 138 miles south. They establish fish camps where they trap and process huge schools of arctic char. Photo shows a few families making a port of call in their homemade boats enroute to their summer homes, 20 miles up the fjord from Saglek. |

|

Saglek Airmen Brave Loneliness and Ice

Story by MSgt. William O. Costello Photos by Stowell E. Wright |

|

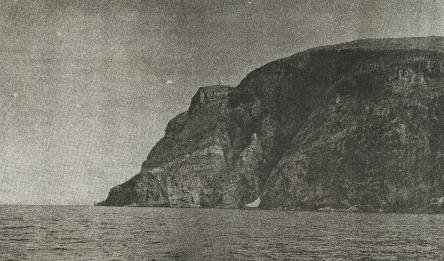

FROM THE SEA

About 1000 A.D, a Viking ship was blown off course and the crew discovered a new land, Today nearly o thousand years later Labrador's formidable cliffs and barren terrain remain almost the same as they did in that distant past. Saglek's radome in the center of this photograph illustrates the towering 1800-foot high cliff from which it broods over the North Atlantic. |

|

VIP Treatment

There are two weekly EPA contract flights between Goose and Saglek. Each arrival is a special occasion, not unlike stagecoach arrivals when the American West was also young and dotted with outposts. A welcoming committee-- some members official, others just friendly and curious-- give each visitor the VIP treatment.

Actually, Saglek is divided into two stations -- upper and lower. The main station is by far the larger but Lower Camp, about five miles down a serpentine road is a vital port of the Saglek complex.

In this age of automation and specialization, Lower Camp offers a nostalgic glimpse of individual ingenuity and diversified talent. Each man has dual positions but TSgt. Sylvester Lehrter qualifies as a multi-specialist. The 37year-old noncom from Aviston, Ill., is officially NCOIC of Lower Camp but that's just a starter. Sergeant Lehrter also conducts radio and tower operations, directs vehicle maintenance, operates the Saglek airport, handles protocol,., serves as beach master during the short shipping season, makes weather reports and supervises the dining room.

POL Operations

Activity at Lower Camp was just returning to normal following an extensive fuel unloading operation. SSgt. Dennis A. Lee, on loan from Sondrestrom AB in southern Greenland, was in charge of petroleum, oil and lubricants (POL) operations. He explained that the Canadian tanker Skua, seen earlier from the air, had off-loaded 129,342 gallons of diesel oil. Earlier another tanker had deposited nearly 150 thousand gallons.

Although he is on temporary duty, Sergeant Lee was already a key member of Lower Camp and, like everyone else, he has multiple duties. The veteran noncom acted as fire guard for the DC-3 and also assisted in unloading baggage and mail. |

|

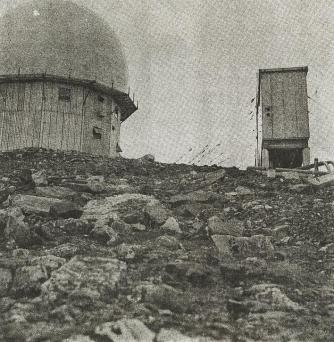

LANDMARK

Saglek's distinctive landmark from land, sea or air is its towering radome, which constantly scans sub-arctic skies for thousands of square miles. As with all Saglek's buildings, utility building at right is secured with heavy-duty cables and shackles. Without these safeguards buildings could easily be swept away during wild winds experienced each winter. |

|

The trip to Upper Camp is pleasant, especially if the driver acts as both chauffeur and guide. MSgt. Charles L. Edwards, food supervisor at Saglek, is hard to beat. A personable, articulate man, Sergeant Edwards is also a student of the area. He described points of interest, their history and ended the trip with the first of many excellent meals in his main dining room.

Food is vital at isolated stations. Sergeant Edwards knows this well and never lets his nine-man staff forget it. Preparing meals for 120 men is a radical change for the 19-year veteran. Prior to his Saglek tour, Sergeant Edwards was stationed at Mitchell Hall, the glass palace of the Air Force Academy, which seats 2,500 cadets at each meal.

The local fire department is just one of many activities that turn the mountain top installation into a self-sufficient city. It has its own warehouses, bakery, department store (BX), restaurant, bowling alley, closed-circuit radio station and Saglek even has its own mayor. The title is honorary but well-deserved. He Is George "Pop" Foster. A civilian employee from Amherst, Nova Scotia, Pop has been at Saglek for more than six years. Mr. Foster is a refrigeration specialist but he's also the unofficial unit historian and custodian / disburser of the Saglek fish fund.

Fishing is a Fringe Benefit For a short period each summer, Saglek offers some of the finest fishing on the North American continent. The unit maintains a rustic fishing camp about 25 miles up the fjord which is available to all personnel. It is not unusual for six or seven men to bring back 200 pounds of delicious arctic char after a weekend trip. These go into Pop Foster's freezer for subsequent distribution to appreciative visitors and friends throughout the GADS area. |

|

Colonel Solomon's words take on added impact when standing alone at twilight near the cliff. A dull golden glow lights the radome nearby. From within a slight mechanical hum is heard as the search radar revolves constantly, probing arctic skies. No other sound or sight of civilization breaks the stillness.

Four hundred trackless miles to the north lie Baffin Bay and Greenland; east is the inky blackness of the North Atlantic stretching to Europe; to the west are hundreds of miles of uninhabited territory reaching across Labrador into Quebec to the distant shores of Hudson Bay. South from Saglek, the nearest civilization is a small Eskimo village, 138 miles away.

This has to be one of the loneliest spots on earth. |

|

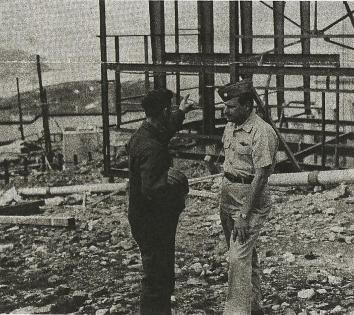

CONSTRUCTION OF GYMNASIUM

Against a background of endless miles of trackless territory Lt Col. R. F. Solomon, commander of the 924th AC&W Sq., confers with Austin Balke, carpenter foreman, one of the 42 construction workers building Saglek's new gymnasium. With a short summer, time is a major factor in outdoor work. Colonel Solomon is constantly checking to see they are on schedule. He received an affirmative answer and the gym was completed this month by Colonial Briard Company of Montreal.

Yaro adds the following note:

The Gym was completed by November 1965. Around thanksgiving we had winds in excess of 200 mph that blew off the gym roof. We had to scramble to get everything out. It was not just the gym but also the library, music record library and recreational facility. We also had to ensure the Gym floor was not damaged until civil engineers could fly in and make permanent repairs. |

|

But the fishing season, and all outdoor recreation, ends quickly at Saglek. The hostile climate comes early and stays late. On the Fourth of July this year while Goose AB basked in warm sunshine, Saglek received five inches of snow. Average temperature during the long, gloomy winter is minus 20 degrees and frequently dips past minus 40 degrees. The frigid weather at Saglek is accentuated by icy blasts which howl across the water. Winds often reach 100 knots and shattered all record. (and the wind gauge) last December when they soared to more than 200 miles per hour.

Forced to remain indoors, loneliness and boredom could easily become an occupational hazard. That's why Saglek, and all remote sites, put strong emphasis on morale, arranging programs and extensive hobby facilities. There is a wide variety of recreational pursuits. Included are a fully equipped photographic lab, billiards, library, games, arts and crafts, closed circuit radio and first-run movies.

"We are well aware that creating and maintaining morale is of special concern at isolated stations," says Lt. Col. Richard F. Solomon, who assumed command of remote Saglek following command of a semiremote radar station in Oregon."Sure, we have good recreational facilities, and they're going to improve," he says. "But don't overestimate their importance because all the entertainment in the world couldn't change one basic fact: this is a tough assignment and it takes a special kind of man to spend 365 days here, literally apart from the outside world and family. We can do just so much and then each man is on his own." |